Stockholm Syndrome

How the Swedish Capital Became Europe’s Unicorn Powerhouse

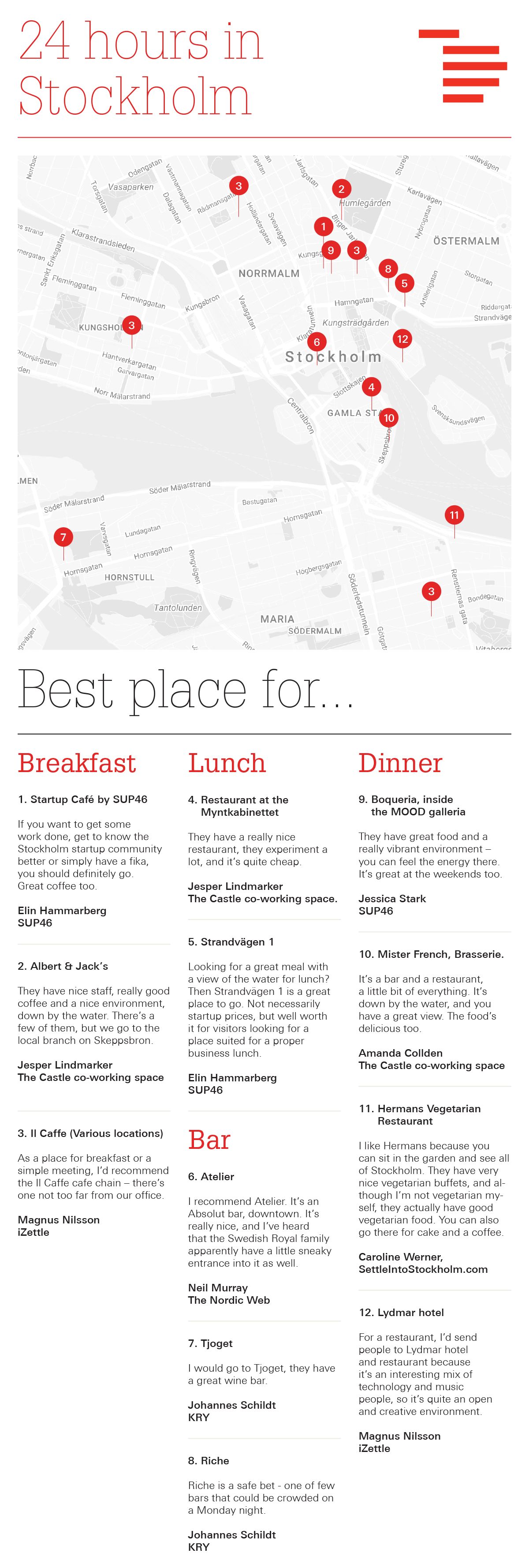

When it comes to tech startup co-working spaces, Stockholm has an embarrassment of riches – and not just in numerical terms (there are thought to be at least 20 in the city), but in the sheer variety of what’s on offer too. Whether founders are hardware-focussed, simply looking for a coffee-fuelled freelancer hangout, or want to belong to an experimental community of 250 people, housed in a castle alongside ‘lifestyle entrepreneurs’ and even a circus acrobat, then the city has them covered.

The best-known of Stockholm’s co-working spaces, however, is startup hub SUP46 (Startup People of Sweden), which was founded in 2013, to hothouse the best of the region’s tech talent. Located in the heart of the city’s downtown area, SUP46 “cherry-picks” around 50 startups at any one time, ranging from seed stage to post-Series A companies, only accepting about 10% of those who apply for membership.

Over the past year, its members have been drawn from 36 nationalities, it has welcomed more than 30k visitors from around the world and hosted 245 tech/startup events. All of which, says Jessica Stark, SUP46’s CEO and cofounder, is indicative of the way Stockholm’s grassroots tech scene has recently ignited. “I've been working with entrepreneurs here for over fifteen years and it’s only in the past few years that the scene has really started to come together,” she says. “People now support each other, there are far more startup hubs and events across the city, and many more investors, which together have made Stockholm feel much more like a major ecosystem.”

Stockholm has produced many successful tech companies including Skype, Spotify, iZettle, Mojang (Minecraft), Klarna (online payments) and King (Candy Crush).

Evidence of how Stockholm has indeed become one of Europe’s ‘tier one’ tech centres isn’t hard to come by. One key indicator is investment momentum, which has undoubtedly reached escape velocity. According to research by The Nordic Web, Stockholm Business Region (which is wholly owned by the city of Stockholm), and SUP46, total investment in Stockholm’s startups for the first six months of 2016 reached $1.2bn, eclipsing the total amount raised throughout 2015 ($892m). In fact, investment has quadrupled since 2014, which saw a comparatively meagre $311m invested in the city’s startups. “I think it fair to say that Stockholm and Sweden have elevated themselves above everywhere else in the Nordics now and definitely should be considered on a level with London and Berlin as one of Europe's main ecosystems,” says Neil Murray, The Nordic Web’s founder.

But it isn’t just investment which is flowing into Stockholm. According to research by the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce, the city is also the fastest-growing in Europe, with its population predicted to surge by 11% to over 1m people by 2020. Alongside this, says Joseph Michael - head of startups/tech at Invest Stockholm (part of the City of Stockholm) – at 18%, the city has the highest proportion of tech workers in Europe, and is continually attracting new tech expertise too. Citing research by LinkedIn, he adds: “Pick any city, even London, and compare how many people from London are moving here and from here to London, and it’s always positive in Stockholm’s favour. So not only are we attracting a lot of capital, but people and talent too.”

Similarly, in its Nordic Analysis (published in November 2015), CITIE, a partnership between Nesta, Accenture and the Future Cities Catapult, found that Stockholm, on a per capita basis, lagged only Silicon Valley “as the most successful producer of technology companies valued at over $1bn. These include familiar household names such as Skype and Spotify, alongside the newer entrants to the tech unicorns club of Mojang (Minecraft), Klarna (online payments) and King (Candy Crash).” (The latter, alongside mobile payments company, iZettle, are among Index’s investments in Stockholm.)

So what are the factors that are underpinning Stockholm’s irresistible rise? Index partner Ben Holmes points first to the aforementioned “fantastic winners” that the Swedish capital has produced. “One of the key things about an ecosystem buzzing is that they have to have a few star companies that perform extremely well,” he says. “And it's really probably London and Stockholm, which - on that criteria - are the most compelling hubs in Europe. The ones we’d point to in Stockholm are obviously King, a games business which did phenomenally well and, although they have a London office, a lot of their creative development was done in Stockholm. And obviously you've got Spotify, which is an extremely well-known globally successful company to come out of Stockholm. Then there are many other highly-regarded companies there, many of which are app businesses, where product design is a key part of the success of the company, including iZettle and Mojang with Minecraft, which was an incredible and slightly bizarre product that came out of that market.”

Madhu Murgia from the Financial Times interviews Magnus Nilsson, co-founder of iZettle, Index's Ben Holmes and co-founder of digital health startup KRY Johannes Schildt

And it’s product, continues Holmes, which is the common denominator across Stockholm’s hit companies. “Building a good product requires both left and right brain, and without wanting to generalise too much, I think that the experience I've had from working with companies in Sweden is that there's generally a very collaborative relationship and operating process within all companies there. There isn't necessarily this very pronounced divide that you see elsewhere, between who’s a coder or developer, who’s a commercial person and maybe who’s a creative and designer. There's more of an equilibrium between those different mind-sets within Swedish companies. And there are many individuals, who have elements of both the technical and the creative talent. A lot of people seem to have come through the education system there, who are both commercially-savvy and good at product design, as well as having sufficient technical understanding so that they integrate very well with the developers in their companies. A great example of this is a young company we recently backed called KRY, a digital health startup which connects patients with healthcare professionals for consultations via video.”

Ben Holmes: “Building a good product requires both left and right brain, and without wanting to generalise too much, I think that the experience I've had from working with companies in Sweden is that there's generally a very collaborative relationship and operating process within all companies there.

Significantly, LinkedIn’s study, says Michael, also found that the standout specialist skills, across all sectors of Stockholm’s workforce, are User Interface and Software Engineering. “That’s the combination that we see has led to all these amazing products. We value design in Sweden. I personally believe it comes from us having a close relationship with nature. Swedes tend to have a holiday house, where we go in the summer and spend a lot of time surrounded by nature. We appreciate design and we're very good at it. Combining that with our engineering background and our appetite for innovation in the tech space has created a situation where all of these different products have been developed,” he argues. “For instance, what a lot of users attribute the success of Spotify to is its very simple, very clean and, in a way, revolutionary user interface design.”

The next key factor behind Stockholm’s success is the way increasing numbers of young people actively want to work in startups. Just a few years ago, people went to the Stockholm School of Economics because they wanted to work in finance, says Johannes Schildt, CEO and cofounder of KRY. “Now everyone wants to work in startups. That has changed a lot over the last few years – and, again, that’s mainly due to Skype, Spotify, King and so on.”

In addition, he says these celebrated companies have spawned a generation of founders and early employees who have the disposable cash to back the next generation of talent, making the virtuous circle self-perpetuating. “There are many more people about now, who’ve made money from the Spotify share options programme, or from King’s IPO, or other companies, who are willing to invest a bit of it as angel investors in early stage companies. That’s great for the community.

There are a number of what might be termed ‘secondary’ ingredients in Stockholm’s rise too. For Schildt, one of these is Sweden’s population size of just 9.8m, which he deems a competitive advantage. “Because we live in a small country, you have to go to other countries in order to build a big company, so many people tend to think globally from the start,” he says. “In the UK, you can still build a significant business by just being in the UK, but in Sweden you have to go abroad – and I think that’s a benefit.”

IKEA's head of design at Index's founders event in Stockholm shares his experience running a team of 350 designers responsible for 2000 new products launched every year

Another hard-to-pin-down yet important ingredient, according to SUP46’s Stark, is the lack of hierarchy in Swedish society, which explains why teamwork comes so easily and instinctively to startups. The attitude among early stage companies, she says, tends to be one of working collaboratively towards the common good, and prioritising the company’s success, over that of individuals. “What [IKEA founder] Ingvar Kamprad did was to really focus on building a super-strong company culture, where you really feel like you are involved,” she says. “And I see something similar in the teams here. Swedish startups are just really good at getting everyone involved, and making them feel like they’re part of a team.”

iZettle cofounders Magnus Nilsson (left) and Jacob De Geer (right) with colleagues in Sweden

The informal, non-hierarchical nature of Swedish society also makes it easier for founders, at the earliest scoping-the-market phase of company-building, to pick up the phone to whoever they like. Magnus Nilsson, cofounder and COO at iZettle, recalls doing just that when he and cofounder Jacob de Geer decided to find out all they could about the payments sector by meeting with the industry’s leaders. “Within two to three weeks we’d met with everyone we wanted to meet, because whoever you call - whether it’s the person you want to speak to themselves or someone who knows them - will nearly always meet you,” he says. “Unlike in lots of other countries, where you wouldn’t get to see them - because as a startup you’re too low down the ladder - Sweden is a much more tightly-knit society.”

“Within two to three weeks we’d met with everyone we wanted to meet, because whoever you call - whether it’s the person you want to speak to themselves or someone who knows them - will nearly always meet you.”

Yet the flipside of having a more egalitarian society, Nilsson continues, is that there is often “a certain degree of contempt” directed at Swedes by people from other countries over what’s perceived to be foot-dragging and procrastination over decision-making -- typically caused by the need to build consensus within Swedish firms. “In Swedish businesses there’s a principle that you don’t go in and tell people what to do [as a boss], but rather you try to convince them that ‘X’ is a very good idea,” he explains.

“Of course that’s exaggerated, because there is always a boss somewhere who will in the end say ‘This is what we’re going to do’. But the upside to the decision-making process, itself, taking longer is that once a decision is made, efficiency and productivity tend to be much higher in Swedish companies because people are more aligned. [By contrast], in many countries where companies have a hierarchical structure, often a failed product will continue to be produced for some time, because someone’s decided it should, even if everybody knows it’s a dead horse. In Swedish companies, we have less of that, due to the fact that if something’s wrong, you will tell the boss - you won’t just shut up and accept it.”

The final ingredient – and, arguably, most significant of all - was a particularly far-sighted Swedish government policy, which can be traced back to the 1990s, where the cost of personal computer purchases were subsidized via tax deductions, thereby enabling businesses to buy computers for their employees’ personal use. This initiative had a huge impact on computer literacy, and -- coupled with the harsh Swedish winters, which tend to keep families indoors -- meant that a generation of children grew up with impressive computer skills. “That [policy] allowed a lot of people who would have normally not been able to afford a computer, to buy one,” says Invest Stockholm’s Michael. “It’s a great example of what happens if we make technology available to everyone. And it’s been a huge contributory factor, more than a decade later, to [Stockholm’s success as a tech hub].”

Michael also cites a second policy as having a similar impact on the city’s subsequent tech startup surge: a project known as ‘Stokab’, which launched in 1994, which leases fibre optic networks to telecom operators, businesses, local authorities and organisations, on affordable terms, to boost IT development and growth in the Stockholm region.

“Twenty years ago, the city made a decision to take full responsibility for the technical infrastructure the same way we do for physical infrastructure, such as roads,” he explains. “So the city decided to build out a fibre network and - although it wouldn’t offer any services on it – we would make sure that the whole city was connected. Because it was going to be a passive network, it meant anyone could provide services on top of it. Today, if you live here in Stockholm, you have over 30 different options for internet service providers at home and more than 120 providers to businesses, which drives the cost down. 95% of all of the homes in Stockholm have access to the fibre network and 100% of offices. And the Stokab model is being replicated all over the world.”

He adds: “Stockholm was also the first place for 2G, 3G and 4G mobile technology and we're working on 5G as we speak. You can try it out right now. All of these innovations and technologies are the foundation for the businesses and tech startups we see today.”

Located in the shadow of the Royal Palace, in the heart of Gamla Stan, Stockholm’s historic centre, the Castle is a co-working space with a twist. If SUP46 wants to hatch the next wave of Nordic unicorns, the Castle is busy building a free-flowing community, among its sumptuous rooms and elegant hallways, not just of tech entrepreneurs, but of freelancers, lifestyle startups, artists, and even a circus performer.

Yet despite the abundance and variety of co-working spaces and the blizzard of tech industry events - ranging from SUP46 Happy Hours to ‘Silicon Vikings’ and Symposium – Stockholm, just like any other hub, has its fair share of seemingly intractable problems too. In particular, there was broad agreement amongst almost everyone interviewed for this article that there are two longstanding issues, which are in danger of holding the Swedish tech ecosystem back.

Housing in Stockholm is a major problem that's holding the tech ecosystem back

The first centres on the city’s chronic shortage of affordable housing to rent. According to Jesper Lindmarker, the Castle’s cofounder, the situation is “absolutely” a major problem. “Among friends, and everyone of my generation, it’s really hard to find a place,” he says. One entrepreneur and Castle resident, Caroline Werner, even founded her business, SettleIntoStockholm.com, on the premise that newcomers to the Swedish capital need hands-on support not only with learning the language (her speciality), but also navigating the rapids of finding a place to live, particularly given that the DIY alternatives, such as responding to ads on blocket.se, a Swedish version of CraigsList, are doomed to failure. “The people renting [apartments] out get thousands of applications – so you never hear anything back from them.” Which is why the only reliable route is word of mouth, she says. “Most of my clients that I've helped to find an apartment have found it through people I know or that they’ve got to know.”

It’s an all-too-familiar gripe; even Stockholm natives struggle to find a place to live anywhere central. “It’s impossible to find a decent apartment,” confirms KRY’s Schildt, adding that housing has even become a major pain point for tech companies seeking to hire non-resident talent. “If I tried to recruit you, you’d probably have to live an hour outside Stockholm or pay half your salary in rent. It’s insane, actually. If you’re coming to work in Stockholm for a couple of years, you probably won’t want to buy an apartment, you’ll probably want to rent one. And [that means] you have to go to the second-hand [subletting] market, which is extremely expensive. We have these public queues where you can wait in line for a rental apartment to become available. I’ve been in a queue for one apartment building for 26 years, and still haven’t got an apartment there.”

And while the housing issue is seriously impacting upon Swedish start-ups’ ability to recruit talent from abroad, that situation is being exacerbated by problems and delays over acquiring work visas for non-EU citizens, says SUP46’s Stark. “We’ve had some examples where it has taken over a year to get a visa accepted. And it’s pretty common that you have to wait nine months. [When combined with] the housing situation, the fact that it can take a really long time to get a visa makes finding and attracting talent to move here the number one problem.”

The second major problem, centres on the Swedish tax regime, and the way that in Sweden, stock options - used by Silicon Valley, for example, to coax top talent to a company – are (heavily) taxed as income from employment. In fact, both issues came to a head earlier this year, in what must have been one of the least likely protests of all time, when managers and employees from leading Swedish tech companies, including Spotify, took to the streets outside parliament. “I hope politicians will take more proactive measures to change the conditions for tech startups,” one industry protester told Bloomberg. “We have a situation with housing that’s difficult and it’s hard to attract specialists in terms of being able to pay them with options because of the tax rules.” Spotify’s Nordic MD, Jenny Hermansson, even warned that Stockholm could lose jobs to rival tech hubs, such as London and Berlin, as a result. A review of the current system, ordered by the government in 2014, is set to introduce more favourable rules around stock options for startups, but they currently won’t apply to growth stage companies, according to a tech specialist Swedish law firm.

Index’s Holmes argues that not being able to easily incentivize key staff with the same sort of structures which are common in the US and the UK is problematic for Sweden in the long term. “There is some pressure to change that politically, but personally I'm not convinced that is likely to be a priority for the current government in Sweden,” he says. “However, we would love to see that change because the very senior founding executives in companies can usually do quite well financially, but many of the very critical early, subsequent and later employees often don't do as well as they would have had they worked in a US company.”

Meanwhile, on Stockholm’s housing crisis, Invest Stockholm’s Michael insists that the city is “building like never before”. He says: “We're building 30k new homes by 2020, and 140k new homes by 2030. These are numbers you can't compare to any other city. So the city is doing a lot to build, but it does take time. We're also working with private real estate owners, who are supporting this in different ways, including by opening up empty apartments to the startup community.

“But ultimately I think the debate [over housing] is really about pace. The technology sector is moving so fast right now, everywhere in the world, but especially in Stockholm, that all of the other sectors, including construction, have a hard time keeping up. Of course we want the city to grow and support the tech community. But [we’re aware] it's not quick enough, compared to how fast the development is going in the community itself.”

Posted on 08 Dec 2016

Published — Dec. 8, 2016

-

-