Real Time: Aaron Katz’s Journey from Salesforce to ClickHouse

Steve Katz lived the classic salesman’s life. For over 30 years, he climbed the ladder at Xerox, selling copy machines for what was then one of the world’s leading technology companies, rising to regional and then district sales manager. Eventually, he moved into a senior management role at Xerox Document Systems, colocated at the company’s famed Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), where he marketed many of the innovations we take for granted today—the laser printer, the graphical user interface (GUI), Ethernet, and Xerox’s STAR networked workstations and servers.

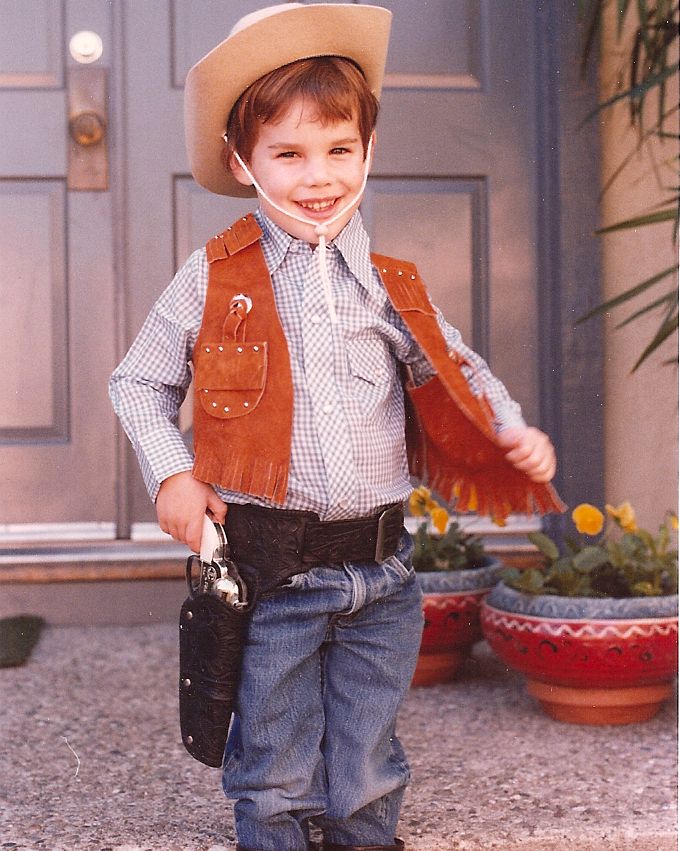

Every morning, Steve’s son, Aaron Katz, would watch his dad put on a suit, grab his briefcase, and hop in his 1962 Camaro. Sometimes Aaron would tag along. Sitting in his father’s office or roaming the halls of PARC, he was too young to fully appreciate the innovation unfolding around him (“I was fortunate to be in and around Silicon Valley as it formed,” he says decades later), but the rhythm and opportunity of a life in business made a lasting impression.

“I could see the quality of life he provided for our family, the joy he brought home when he would close a deal, or he would get promoted, or somebody on his team would achieve something great,” Katz says. “I thought that seemed like a career worth pursuing.”

Katz was born at El Camino Hospital in Mountain View in 1976. He grew up in what he calls a “run-of-the-mill 1980s middle-class” environment. “It wasn’t like we were living month to month, but we did have a very tight budget.” He credits his parents with exposing him to a wide range of experiences that included plenty of time outdoors—hiking, cycling, fly fishing, cross-country skiing (downhill skiing was too expensive)—and biennial trips to England to visit his mother’s family. Ellen Cross had emigrated to the U.S. as an au pair in the 1960s, later working at Xerox, where she met Katz’s father. It was those visits to London, and his mother’s influence more broadly, that added an international inclination to Katz’s early interest in business.

After high school, Katz enrolled at UC Davis, following in the footsteps of his sister Liz. Born 18 months apart, they were “more or less raised like twins,” he says. “She was my best friend growing up and the best possible role model for me.” He studied Managerial Economics while minoring in English—his mother’s suggestion to “graduate with marketable knowledge and the ability to write”. In his final year, he interned at Sun Microsystems, one of the fastest-growing and most innovative tech companies in Silicon Valley. After graduating in 1998, he turned down offers from Sun and Intel to accept a consulting role at PeopleSoft, where he was assigned to a project in Europe doing Y2K testing (at the time, many feared all computers would crash at the turn of the century).

After some time overseas, however, his FOMO started to kick in. It was the height of the dot-com frenzy, and as Katz puts it, “If I had stayed in Europe, I would have missed the tech renaissance that was happening in San Francisco.”

He moved back to the Bay Area, joining a startup with some colleagues from PeopleSoft. “It was your textbook dot-com experience,” he says. “Raised a ton of capital, spent a ton of capital, garnered a massive valuation which never materialized.”

In the winter of 2001, he found himself unemployed from the tech sector and waiting tables at a Mexican restaurant in Tahoe City while awaiting acceptance to business school. Then the rejection letters started arriving—first Stanford, then Harvard, Kellogg, Wharton, and finally waitlisted at MIT. He was 25 and more or less broke. “Like many in the tech sector coming out of that period, we were quite disenfranchised,” he says. “We had this incredibly quick ascent, and then an even more rapid and jarring descent.”

“If I had stayed in Europe, I would have missed the tech renaissance that was happening in San Francisco.”

—Aaron Katz, ClickHouse

He returned to San Francisco, where his sister suggested he look into jobs at Salesforce. The company was only a few years old, but Katz was familiar with the product, having used it at his previous startup. He’d also begun to see the convergence of the internet and enterprise software, and he sensed potential in that shift. He sent in an application. A few days later, he received a form rejection email from recruiting. “Selling starts with no,” he says.

Through his network in San Francisco, Katz managed to get an interview with Salesforce’s head of sales, which led to a meeting with Marc Benioff. At the time, the company had around 150 employees, and Benioff was still personally interviewing every prospective hire. Even so, Katz knew he wouldn’t get much time. In Benioff’s office on the third floor of The Landmark at One Market, the founder and CEO asked a single question: “Why should I hire you?”

Katz, knowing Benioff’s background as a Larry Ellison disciple in Oracle’s famously cutthroat sales culture, said simply, “Because I’m going to outperform everyone else.” In hindsight, it was a bold proclamation—Katz describes the early sales culture at Salesforce as “the largest concentration of remarkably talented salespeople our industry has ever seen.”

But for Benioff, that was enough. He shook Katz’s hand and said, “Welcome to Salesforce.”

Rising tide

Frederic Kerrest joined Salesforce around the same time as Katz, in a similar Sales Engineer role (what would now be called a Solution Architect). He describes the environment as “very collaborative,” with everyone working together to learn the technology and figure out how to serve customers. He and Katz became friends, not just teaming up in sales cycles, but getting to know each other outside of work.

“Neither of us were typical sales guys,” says Kerrest, who went on to found software company Okta in 2009. “That technical background starting out turned out to be very helpful in our careers as entrepreneurs. I know in Aaron’s case, with ClickHouse, they would not have been able to do what they’ve done without his technical proficiency.”

“As a software company, you can talk about all the benefits of your technology—faster, cheaper, better, more feature-complete. But if customers don’t advocate on your behalf, then it’s just a baseless claim any company can make.”

—Aaron Katz, ClickHouse

In 2003, six months after joining Salesforce, Benioff promoted Katz to lead small business sales for the western U.S. Later that year, the company hosted its inaugural Dreamforce conference at the Westin St. Francis hotel in downtown San Francisco. Around 500 people attended, including speakers from Salesforce’s early enterprise customers. Hearing executive leaders talk about the value they were getting from the product, a light went on. “There is no better value claim than one provided by a customer,” he says.

That customer obsession—something Katz says he learned directly from Benioff—has shaped his approach to company building. “As a software company, you can talk about all the benefits of your technology—faster, cheaper, better, more feature-complete,” he says. “But if customers don’t advocate on your behalf, then it’s just a baseless claim any company can make.”

Salesforce went public in the summer of 2004. Later that year, Benioff asked Katz if he’d be willing to move to Singapore to help establish the company’s APAC headquarters. It was meant to be an 18-month posting. Katz talked it over with his then-girlfriend, now-wife, Johonna, and they agreed it was an opportunity worth taking.

Katz’s directive was clear: “Set up the office, build a team, find your successor, come home.” But the APAC job, he says, “got really big, really fast.” As Salesforce grew, so did Katz’s mandate for the region. He expanded Salesforce into India, Hong Kong, South Korea, and other countries across Asia Pacific.

“It was obvious I couldn’t complete the job in 18 months,” Katz says. Eighteen months turned into four years. He and Johonna were having the time of their lives—weekending in Bali, traveling around Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam. During a business trip to Australia, Katz decided to stop in New Zealand to go fly fishing. He landed in Christchurch in the middle of the night. After reviewing his passport, the authorities detained him, matching his travel pattern to the infamous “Golden Triangle” of the opium trade.

“I work for Salesforce,” Katz explained. He showed them his notebook and laptop, gave them a number they could call to verify his employment. They put him in isolation. After four hours, an officer informed him they had tested his bags and found traces of narcotics. “Have you lost your fucking mind?” Katz said. “I’m a tech exec, not a drug trafficker—and for the record, I have never taken synthetic drugs!” Two more hours passed before another officer came in and released him without explanation. “By then, the sun was coming up, and I was running on no sleep,” Katz says. “I grabbed my gear and went fly fishing.”

By 2009, he and Johonna had gotten married and were ready to start a family. After one more stop—this time in Dublin, Ireland, where Salesforce needed help expanding into continental Europe—they returned to San Francisco. Katz worked under Brian Millham, one of Salesforce’s first hires and later president and COO until his retirement in May 2025. Millham describes Katz as “the consummate professional” and a “grinder” who never accepted defeat.

"He was just one of those people you treasure as a leader—very competitive in a good way and accountable to what he said he was going to do.”

—Brian Millham, ex-Salesforce COO, on Katz

“It would be late in the quarter and I’d be looking at the forecast, saying, ‘I don’t know how Aaron’s gonna get there,’” Millham recalls. “And somehow, some way, he would pull it off. He’d call in the right customer, leverage the right relationship, tap the right people inside the company to help him get the deal done. He was just one of those people you treasure as a leader—very competitive in a good way and accountable to what he said he was going to do.”

In 2012, Katz took over Salesforce’s Latin America operation, in addition to overseeing Enterprise Corporate Sales in the U.S. and Europe. His 12-year run at the company culminated with the 2014 World Cup in Brazil. By then, he was 38 and ready for a new challenge. “I had experience in every major international market, all of the different market segments within those, and all the different industries,” he says. “I’ll always be grateful to Marc, who I believe to be one of the best CEOs of our lifetime. I just felt like I had to leave home professionally.”

Katz was one of many employees who had effectively grown up at Salesforce. He wanted to see if his success had come from joining a great company—a rising tide lifts all boats—or if he could replicate it on his own. “At that point, I knew I wanted to be in the top job running all the go-to-market aspects of a company,” he says.

"For Aaron to leave took a lot of gumption and, frankly, willpower. It meant taking a bet on himself.”

—Frederic Kerrest, Okta co-founder and former Salesforce colleague

Even so, the decision wasn’t easy. “I had worked for 12 years to get to this SVP role,” he says. “I had hundreds of people working for me, a seat at the table with Marc and the exec team, all of this equity still vesting, all these financial reasons not to leave. There are a lot of cautionary tales where people left the company and regretted it.”

Katz’s friend Kerrest, who left Salesforce in 2007, saw things similarly. “When you’re doing very well in a big company like Salesforce, they do a lot of things to keep you. For Aaron to leave took a lot of gumption and, frankly, willpower. It meant taking a bet on himself.”

Millham, for his part, saw the writing on the wall. “I was incredibly disappointed when Aaron left Salesforce,” he says. “I tried my hardest to keep him. At the same time, I knew this was the next step for him—that he was ready for a bigger job.”

Championship pedigree

In 2014, Katz joined Elastic as CRO. Ever since starting his career as an intern on Sun Microsystems’ JavaStation project, he’d been interested in getting back into infrastructure. Index partner Mike Volpi and Benchmark’s Peter Fenton were both board members at Elastic, and the two pitched him on the influence and opportunity he would have leading revenue at what was then an early-stage, open-source infrastructure startup.

“They refreshed my thinking regarding the market opportunity of a database—the diverse set of use cases, the broad competitive landscape, and the clear advantages of open source, both from an innovation and distribution standpoint,” Katz says.

Volpi recalls being impressed by Katz’s background, especially his years overseas at Salesforce, which proved relevant to Elastic, a Dutch-owned company. “That turned out to be very important at ClickHouse as well,” Volpi adds, noting the company’s international team and the nuances of managing different business cultures—an area where he says Katz shines.

From a product perspective, there were parallels between the bottom-up adoption Katz saw at Salesforce and what Elastic presented. “I was able to execute a playbook I had learned before,” he says. Individual contributors—in Elastic’s case, developers—became internal champions, community drove distribution, and a well-structured sales org converted that traction into revenue.

But infrastructure wasn’t applications, and not everything translated so neatly. One of the biggest hurdles at Elastic, Katz says, was navigating the shift from self-managed software to a managed cloud service. “It can be extremely arduous, painful, slow, and expensive… and that assumes you develop a differentiated service,” he says. Many customers still wanted to run it in their own data centers, even as the broader market moved to the cloud. The buyer persona was also more complex, as the individual using the software was often different from the economic buyer. Elastic had to cater to both.

“Aaron is always asking not just how we’re going to close this deal, but why is the customer signing with us? What’s the use case? Who’s the competition?He’s like a product marketer wrapped up in a salesperson’s body.”

—Tanya Bragin, ClickHouse

Tanya Bragin joined Elastic’s product team shortly after Katz came on board. While Katz spent much of his time on the road scaling the sales org—Bragin laughingly describes his persona then as the “glamorous executive jetting around the world”—they worked closely together on sales enablement and the company’s first customer event. She was struck by how customer-obsessed he was, always trying to understand the user’s perspective and the value they were getting from the product. It’s an approach Bragin says has carried through to ClickHouse, where she now serves as VP of Product and Marketing.

“Aaron is always asking not just how we’re going to close this deal, but why is the customer signing with us? What’s the use case? Who’s the competition?” she says. “He’s like a product marketer wrapped up in a salesperson’s body.”

In six years at Elastic, Katz took the business from around $5 million to $500 million in revenue. The company went public in 2018—a moment Katz says he’ll always cherish. “Standing on the podium of the New York Stock Exchange, with my wife, daughters, sister, and parents all there, after so much time and energy went into building the company… it was a very joyful experience and one I’ll never forget,” he says.

Katz, Johonna, and their two daughters at the NYSE for Elastic’s IPO in 2018.

In March 2020, he stepped away from his day-to-day role at Elastic. “I had been blessed with a 20-year career in enterprise software,” he says. Like many during Covid, he did some “serious soul-searching on what I wanted the next chapter of my career to look like.”

In his mid-forties, Katz saw three paths forward. “A, I could stay in my lane and be this mercenary sales leader. B, I could become a venture capitalist, which was kind of in vogue at the time for ex-sales leaders. Or C, I could run a company.”

“I ruled out number one because I had just done it,” he says. “I ruled out number two because it didn’t really satisfy what I love to do, which is team-building and ditch-digging. That left the third option, which was to become a CEO. That’s when ClickHouse presented itself.”

Straight to the endgame

Katz had dreamt of leading a business since childhood, but he knew he didn’t fit the typical mold of the engineering-trained, tech founder-CEO who conceives and builds the first version of the product. “It wasn’t something that was obvious and right in front of me until I had the time and space to really think about what I wanted to do next,” he says.

In early 2021, through a series of introductions, he took a call with Yandex, one of the world’s biggest internet companies. They were looking for advice on what to do with a columnar OLAP database called ClickHouse. Created by Alexey Milovidov in 2009, and open-sourced in 2016, it had since grown quickly in popularity, becoming the database of choice for engineers working on some of the hardest problems in analytics. Katz knew it from his time at Elastic, having seen a number of prominent workloads depart Elasticsearch in favor of the faster, more efficient ClickHouse.

“It really was the database for people who know databases. When Aaron told us he was pulling together a team to commercialize it, we said right away, ‘We gotta go see if we can pull this thing off.’

—Mike Volpi, Index Ventures

Inside Yandex, however, it remained an internal project with no clear commercial path. Katz saw an opportunity. He proposed forming a new company to house ClickHouse as a standalone business. His proposal came with conditions. “It has to look and smell like a Silicon Valley startup,” Katz told them. “Venture-backed, Delaware corp, independent board. And I need full control to build the team and run the business as I see fit.”

That team began with Milovidov. “I’ve worked with many technical founders in my career, but none more singularly focused on the quality of engineering and product than Alexey,” Katz says. In order to move forward, he stipulated that Milovidov and his team of core engineers leave Yandex N.V. to join ClickHouse, Inc., and that they relocate to Amsterdam.

In the meantime, he called his old friend Mike Volpi at Index. The two had kept in touch during Covid, trading ideas and talking opportunities should Katz decide to return to an operating role. He told Volpi he was in discussions with Yandex about spinning out ClickHouse. Volpi, a seasoned open-source investor, had also noticed ClickHouse’s rise, including its adoption at a number of Index portfolio companies. “I don’t think I had to finish my sentence,” Katz says.

“It really was the database for people who know databases,” Volpi recalls. “When Aaron told us he was pulling together a team to commercialize it, we said right away, ‘We gotta go see if we can pull this thing off.’”

Still, Katz felt he needed one more person—a product and engineering leader who had experience designing distributed systems around open-source technology, and who had done so repeatedly at high-quality companies. The first person he thought of was Yury Izrailevsky. The two had met at an Index event years earlier, when Izrailevsky was leading engineering at Netflix. Izrailevsky had since moved on to Google, where he was overseeing a suite of cloud products with a team of more than 1,000 people.

“You just can’t overstate how good Yury is, and you can’t overstate how brilliant Alexey is. They’re very different, but they’re so aligned in terms of the product we want to build, how we go to market, the pace of innovation. As a CEO, it feels like I’m playing chess with two queens.”

—Aaron Katz, ClickHouse

Katz made his pitch. “NFW,” Izrailevsky replied. But Katz, sensing that Izrailevsky might be receptive to the idea, enlisted the help of Volpi and Peter Fenton. In the end, Izrailevsky, who had worked in startups earlier in his career and never quite scratched that itch, decided to download the open-source version of ClickHouse and try it himself. “When I did, I was blown away,” he says. “It was so fast and so slick and so easy to work with.” After two months of cajoling, he agreed to join as ClickHouse’s third co-founder.

Katz calls it the most successful sales campaign of his career. “You just can’t overstate how good Yury is,” he says. “And you can’t overstate how brilliant Alexey is. They’re very different, but they’re so aligned in terms of the product we want to build, how we go to market, the pace of innovation. As a CEO, it feels like I’m playing chess with two queens.”

The new company—ClickHouse, Inc.—was officially incorporated in the summer of 2021 with a $50 million Series A led by Index and Benchmark. Two months later, they raised another $250 million at a $2 billion valuation. In the meantime, the team set a goal of building a managed service in less than a year, rearchitecting ClickHouse into a true cloud-native platform.

“They could have gone the conventional route, offering an ‘enterprise edition’ to self-hosted users and easing into the cloud over time,” Volpi says. “Instead, they went straight to the endgame, taking what Aaron learned at Salesforce and building a managed cloud service that works as well for a solo developer as it does for a global enterprise.”

“In Alexey, you have this brilliant, technically deep database CTO. In Yury, you have an incredibly capable engineering executive who knows how to build cloud offerings. And then in Aaron, you have this customer-focused, data-driven leader who knows everything about go-to-market and raises the bar constantly for those around him.”

—Tanya Bragin, ClickHouse

ClickHouse Cloud launched publicly in December 2022. Within days, it was powering real-time workloads across a broad range of industries, from fintech and healthcare to transportation, cybersecurity, and AI. And that momentum hasn’t slowed. Today, ClickHouse’s customers include names like Tesla, Anthropic, Mercado Libre, Sony, Meta, Memorial Sloan Kettering, Lyft, Netflix, and more than 2,000 others. In May 2025, at the company’s inaugural Open House user conference in San Francisco, it announced $350 million in Series C funding, along with a host of new features aimed at powering real-time analytics for the AI era.

Bragin, who joined ClickHouse in January 2022 and led the development of ClickHouse Cloud, credits the company’s success with what she calls the “magical trio” at the top.

“In Alexey, you have this brilliant, technically deep database CTO,” she says. “In Yury, you have an incredibly capable engineering executive who knows how to build cloud offerings. And then in Aaron, you have this customer-focused, data-driven leader who knows everything about go-to-market and raises the bar constantly for those around him.”

Katz with ClickHouse VP Product & Marketing Tanya Bragin.

The company you keep

It’s just after lunch on June 6th, 2025. Katz is in an Uber en route to a NASDAQ closing bell ceremony at the AWS Builder Loft. He’s talking about servant leadership, a philosophy he learned from Marc Benioff at Salesforce. The Uber is running late, and Katz pulls out his iPhone to send a message. The edges are all scuffed, the screen is cracked down the middle, and the charging port is broken. Katz digs in his backpack for the MagSafe device he uses to charge the phone. It’s broken, too. “My daughters have better phones than I do,” he says with a smile.

“At ClickHouse, he’s had more of a canvas to express that [low ego] leadership style. He holds a firm grip, but he’s become more collaborative and comfortable in his own skin.”

—Mike Volpi, Index Ventures

The beat-up phone feels like a decent metaphor for how Katz runs a company. “I’m at the bottom of the pyramid, and my employees are at the top,” he says. “They’re the CEOs of their individual functions. My role is to enable them and support them to be successful. That means giving them the resources they need. It means removing any obstacles or blockers. It’s removing any politics or bureaucracy inside the company. It’s celebrating their achievements and then promoting them and rewarding them for their performance.”

Bragin sees how Katz supports the team at ClickHouse, but she adds an important caveat: trust. “He’s not one of these servant-leaders who’s always running around asking, ‘What do you need? How can I help you?’ He doesn’t have time for that. He expects leaders to be proactive and self-aware and ask for what they need. If you do that, he’ll have your back.”

Mike Volpi agrees, adding that Katz “drives outcomes, not inputs.” In other words, he’ll set clear and ambitious targets—pipeline, sales, key features by certain dates—and let the team decide how to get there, empowering them to deliver while holding them accountable.

It’s been over a decade since Volpi recruited Katz to Elastic. He says the biggest change has been the development of Katz’s “leadership signature.” Whereas other Silicon Valley CEOs model themselves after “larger than life” figures like Elon Musk or Steve Jobs, Katz is more in the Tim Cook vein—quiet by nature, low ego, happy to share the spotlight. “At ClickHouse, he’s had more of a canvas to express that leadership style,” Volpi says. “He holds a firm grip, but he’s become more collaborative and comfortable in his own skin.”

Katz’s old Salesforce buddy Frederic Kerrest sees similar qualities outside of work. In 2020, Kerrest invited him to join some friends on a backcountry ski tour up Tamarack Peak. Katz didn’t know anyone in the group, but Kerrest assured them he was up for it. At the end of the nearly 4,000-foot climb, they returned to their cars and prepared to head home. Katz opened his trunk and fired up a camp stove. Soon they were all sitting on chairs in the parking lot, eating the extra lunches Katz had packed for everyone.

“That’s a good example of who Aaron is,” Kerrest says. “He’s a hard charger, but very thoughtful and generous. Obviously an excellent professional and shrewd in a business sense, but he understands the environments he’s in and plays well in those environments.”

Katz with Frederic Kerrest, Okta co-founder and former Salesforce teammate.

Brian Millham, who has seen nearly the full arc of Katz’s career, from the time they were peers in Salesforce’s sales org more than 20 years ago, says Katz always held himself highly accountable. “But it wasn’t until later,” Millham says, “that he realized, if you’re going to get to the size and scale you want, you’ve got to rely on people and empower them.”

Katz agrees with that assessment. “When you’re young, you’re pretty focused on yourself,” he says. “Your achievements, your promotions, your compensation. And as you mature, you realize the only way any of that’s possible is through others. You need a differentiated product to sell, which means you need incredible engineers. You need people supporting customers. You need all the infrastructure and scaffolding. Eventually, you figure out that all the other stuff—category, product, market—is table-stakes. What really matters is the people you work with.”

“When you’re young, you’re pretty focused on yourself: your achievements, your promotions, your compensation. And as you mature, you realize the only way any of that’s possible is through others. You need a differentiated product to sell, which means you need incredible engineers. You need people supporting customers. You need all the infrastructure and scaffolding. Eventually, you figure out that all the other stuff—category, product, market—is table-stakes. What really matters is the people you work with.”

—Aaron Katz, CEO & co-founder of ClickHouse

As Katz has built the team at ClickHouse, he’s filtered for the traits he believes make people successful: drive, focus, accountability, a shared vision. “You can be extraordinarily selective,” he says. “That’s the best part of being a CEO. And then when you meet their spouses and kids, and they say, ‘We have a better life as a result of this company, we bought a house we never thought we could afford, we’re living in a community we never thought would be possible, my spouse loves working at your company’—that’s incredibly rewarding.”

For all his evolution as a leader, Katz says nothing changed his perspective like becoming a parent. “It’s no longer about you. You’re a distant second. You’ve got this limited window to influence who your kids are going to be, and you’re the primary influence. It really requires you to think about how you spend your time and who you spend it with.”

“They are such impressive young women, and I like to think I’m reasonably objective,” he says of his two teenage daughters. “I always tell them, ‘I’m so proud to be your dad,’ and they say, ‘I’m proud to be your daughter.’ There’s no better feeling than that. They’re just a constant source of motivation, inspiration, and pride for Johonna and me.”

As the Uber stops to let Katz out, he remembers something his mother used to say: “Introduce me to your friends, and I’ll tell you who you are.” He’s talking about parenthood, but the same rule applies to running a company. “You’re a reflection of who you surround yourself with. If I surround myself with high achievers who have incredible vision and who execute flawlessly, and every single person I hire holds those standards, then naturally the company is going to reflect that. And so will I.”

Published — Nov. 13, 2025

-

-