Behind the Scenes with Deliveroo

Deliveroo has over 1000 employees and operates in twelve countries and over 130 cities.

Deliveroo Editions are hubs that host collections of hand-picked restaurants, all specially designed for delivery.

Deliveroo has a network of over 20,000 restaurants and more than 30,000 riders.

Deliveroo insiders share the story behind the world’s fastest growing food-tech business.

When Rohan Pradhan left the food start-up he’d built as a student at Harvard, he resigned himself to the fact that cooking would only ever be a hobby. Chefstro, his business, had been a platform that linked young chefs to customers wanting pop-up dinner parties on demand. “I learned so much about the challenges that chefs face. They were incredibly talented; I had no idea how hard they work for how little they make,” he says now.

Pradhan, who’d previously worked in consulting and private equity, scaled up Chefstro to 150 cooks before he was snapped up by Amazon. He helped launch its Prime Now fast delivery service in New York and Europe, and loved the customer-centric and performance-oriented culture of the company. But he still felt he had more to give in the restaurant and food sector.

Then he was approached by Deliveroo. “This was a chance to rebuild something that I’d always wanted to do, to create selection where it didn’t exist,” he says. “Deliveroo is not just a logistics business. We live and breathe food; everyone is driven by that shared passion, and our desire to transform the industry. The opportunity is huge.”

Deliveroo have made strides towards realising that opportunity, although the company seems to think the journey has only just begun. Deliveroo was founded in London in 2013 by friends Will Shu and Greg Orlowski, a pair of Americans working in the UK, frustrated by the lack of delivery options for quality restaurants this side of Atlantic. They decided to set up a service connecting restaurants, consumers and their own Deliveroo riders. Will, the CEO, quickly saw that the unusually high urban density of European cities would work to Deliveroo’s advantage, because the company could deliver a high volume of orders on push-bikes and scooters within a restricted area – and ensure the food would be hot and delicious when it arrived.

Deliveroo's first TV ad

Deliveroo is now ten times larger than it was a year ago, when it had 80 employees and operated in just three cities outside the UK (Paris, Dublin and Berlin). Today it has over 1000 employees, operates in twelve countries and over 130 cities, and has a network of over 20,000 restaurants and more than 30,000 riders. It’s also raised a total of $475m so far to continue its growth trajectory.

They haven’t stumbled or morphed into somebody else’s better business model. They’re still pursuing the original vision and proposition. - Neil Rimer, Partner, Index VenturesFigures like this are pretty unusual for a European start-up, and all the more impressive given the complexity of running a three-sided marketplace with so many interlocking digital and physical components. It’s also surprising given Deliveroo’s “meticulous and gradual” approach to expansion, which tackles cities neighbourhood-by-neighbourhood. They only open in a specific zone when they know the selection of nearby restaurants can provide a good offering to the customer.

Photo from the early days of Deliveroo, taken in 2014

So what’s behind all this? “It may be smarts or luck, but they haven’t stumbled or morphed into somebody else’s better business model. They’re still pursuing the original vision and proposition, which is to deliver the best food experience bar none,” says Neil Rimer, a founder and partner at Index Ventures.

Rimer and fellow Index partner Martin Mignot led the Series A investment of £2.7m in Deliveroo back in 2014, and participated or led the company in its B, C and D rounds. “These guys came from a perspective of loving food, and realising what convenience really meant,” Rimer says. He had just ordered eight meals from four different restaurants via Deliveroo. From order to delivery it was less than eight minutes.

Dan Warne, Deliveroo’s managing director for the UK and Ireland who joined in 2014, says the clarity and consistency of Deliveroo’s mission is striking. “That’s a massive learning for me. I’ve worked in businesses where we’ve changed, we’ve tried to pivot right, left and centre. At Deliveroo we never have, even in the tough times,” he said at a private event hosted by Index last September at Second Home, the workspace and cultural venue. “We need to innovate, but that innovation will never stray away from what the mission of this business is.”

Dan Warne, Deliveroo’s managing director for the UK and Ireland, speaking with Jules Coleman at Index Ventures event at Second Home

At Deliveroo’s head offices in Bloomsbury, food culture is visibly baked into everything they do. An airy communal kitchen dominates the main workspace, where people on laptops chat over a wooden counter and busily unbox the Deliverooed food that arrives in a stream throughout the day. The original scooter that Shu used to use to make deliveries around London has been spray-painted matte gold and mounted on a podium, a gesture that everyone in the business, from the CEO down, is expected to get their hands dirty. Every Friday, the company runs what it calls “Ride Together” – where over 20 people from the main office jump on a bike to do lunchtime deliveries. Shu himself continues to do deliveries every week.

Trust with accountability

The emphasis on individual freedom is key to how Deliveroo has managed the challenges of scaling up so fast. The company’s philosophy is to give everyone a sense of ownership over their own work, and lots of scope for creativity in how they achieve their business objectives.

It’s an incredibly flat hierarchy,” says Martin Mignot of Index Ventures. “Will leaves a lot of autonomy to people, whether it’s his executive team or the managers. He trusts them to be motivated, and they are: it’s a universal product, everyone’s a potential customer, it’s visible everywhere, and has a trendy vibe about it but an affordable quality.

Index Partner Martin Mignot at Index event "Behind the Scenes with Deliveroo". Index led the Series A investment of £2.7m in Deliveroo back in 2014.

Roy Blanga, who spearheaded Deliveroo’s global expansion after he joined as the Managing Director of International in June 2015, notes that independence is vital in a sector as nuanced as food. In Dubai, the company realised it needed “runners” to accompany drivers, because so many restaurants were buried deep inside shopping malls. “It’s really important to adjust your proposition to the local needs: how to approach the drivers, how to approach the restaurants, to be able to tailor the product and the service to what’s necessary for the market to succeed,” Blanga said at Index’s private event in September.

Rob Cooper, Product Manager for Consumer Apps

As Deliveroo sees it, head office acts as a source of knowledge and support to enables local leaders to get on with the job – rather than looking over their shoulder day to day. Once the expansion trajectory was decided, each country manager was fully empowered and accountable for how they delivered their own launches. “By having a structure like this, you can be much more agile and fast at conquering the market,” Blanga says. “You have lots of pockets of excellence, if you’re able to capture those innovations and best practices and disseminate them across the organisation.”

As Deliveroo sees it, head office acts as a source of knowledge and support to enables local leaders to get on with the job – rather than looking over their shoulder day to day. Once the expansion trajectory was decided, each country manager was fully empowered and accountable for how they delivered their own launches. “By having a structure like this, you can be much more agile and fast at conquering the market,” Blanga says. “You have lots of pockets of excellence, if you’re able to capture those innovations and best practices and disseminate them across the organisation.”

At the same time, Deliveroo places huge value on data, and is unapologetic about being analytical in everything it does. Rob Cooper, the Product Manager for consumer apps, encountered this in his job interview. “It was nice question, nice question – then comes: ‘Flip a coin it lands on heads; flip a coin it lands on heads; how many times do I have to flip a coin to be certain to within a 99.9 percent probability that it’s only got heads?’ he recalls. (The answer is ten.) “That kind of interview process makes you realise you’re very valued, and once you’ve got through that, you think that is a job you’ve probably earned.”

Being analytical and data-led, and acting quickly, aren’t mutually exclusive, Warne claims. “Consistent across the whole business is an ability to analyse but not over-analyse,” he says. “In the early stages of a business you have to be prepared to use your intuition; you have to say, I have enough data for the moment, to feel comfortable that I can fire a couple of bullets and see what happens.

While the company devolves a lot of authority to local staff, it’s constantly testing hypotheses and assumptions. “We used to joke a lot about ‘is your pizza calzoned’ – has it bumped up against the box and folded over on itself, like a calzone?” says Pradhan. “So the rider team developed a one-page document on the right way to handle pizza. People really care about this stuff.” On the day we spoke, Pradhan had been assessing a “heat map” of pan-Asian food orders across London, scanning for dark areas whose demographics made them candidates for a Deliveroo launch.

On a grander scale, Deliveroo’s expansion was powered in large part by its launch “playbook”, delivered incrementally from its prior experience in the UK and a handful of European cities. Interestingly, in cities such as Singapore, Deliveroo found that having a challenger can work to their advantage. “The fact we had such a strong competitor there, providing a service that was, in my eyes, not as good as ours, allowed us to quickly scale the business because customers were already used to it, and it was just a matter of giving them something a little bit better,” Blanga said during Index’s private event.

How does the company square a hard-nosed approach to business fundamentals with long-term planning? It’s about the belief that what will ultimately make the business successful is the best possible customer experience. “The next round of growth is not coming from ‘There’s a really cool opportunity out there’; the next round of growth is ‘There are these two problems we haven’t solved for customers, let’s try and solve them,” Pradhan says. “Then it’s about being very honest about what’s working and what’s not working, so there’s this continuous loop of inventing things and pushing on stuff, but discarding a lot.”

Culture eats strategy for breakfast

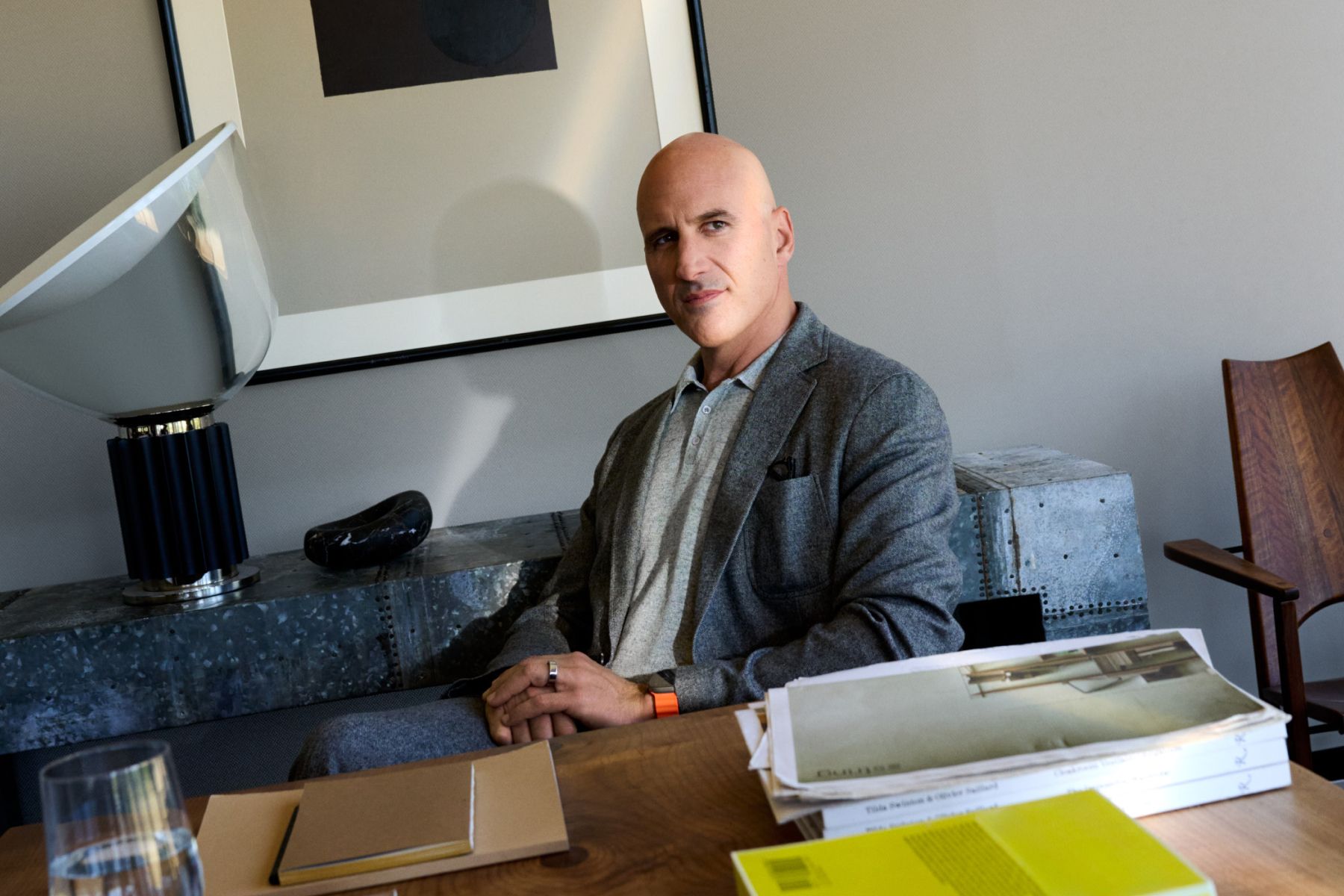

Simon Rohrback, Deliveroo’s Head of Design

Shu’s down-to-earth personality, plus his focus on the big picture, offer hints about how Deliveroo’s culture manages to be both friendly and rigorous. Shu doesn’t use an office, for example, but sits wherever there happens to be a spare chair. “I’ve never been in a business, even in a smaller business, where the founder and CEO is so approachable,” says Simon Rohrbach, Deliveroo’s Head of Design.

Shu’s down-to-earth personality, plus his focus on the big picture, offer hints about how Deliveroo’s culture manages to be both friendly and rigorous. Shu doesn’t use an office, for example, but sits wherever there happens to be a spare chair. “I’ve never been in a business, even in a smaller business, where the founder and CEO is so approachable,” says Simon Rohrbach, Deliveroo’s Head of Design.

Rohrbach – who helped lead Deliveroo’s recent brand overhaul, on everything from a new angular logo to the physical packaging and improved riders’ outfits – praises Shu’s ability to steer the collective thinking of the company. “There’s never a ‘We’ve been mentioned in this newspaper or that newspaper, or we’ve won this or that award’. He’s very good at striking a balance between giving credit where it’s due, and keeping that sense of tenacity, looking ahead to the next year, the next two years, the long term.” (While Rohrbach is talking, Shu walks by with an external visitor, looking for a spare office in which to conduct a meeting. Shu shakes his head and waves away Rohrbach as he starts to stand up, and instead takes a seat on the chesterfield lounge outside in the hall.)

Leila d’Angelo, Deliveroo’s Head of Content, was a reluctant convert. She turned down a job offer from Deliveroo because she wanted to strike out on her own as an independent consultant. Eventually she was convinced to take on some short-term freelance work for the company, and enjoyed it so much that by the time they offered her a full-time job again, four months in, she was ready to accept. “There’s something about Deliveroo that once you’re in, it catches you,” she says now. “I was completely bowled over by it and ready to sign on the dotted line. People are so into working here, it’s infectious.”

Leila D'Angelo, Head of Content

When it comes to recruitment, Blanga says that finding the balance between expertise and experimentation is crucial. He thinks it’s dangerous to go to either extreme, as experience and ambition sometimes work against each other. “If you’re operating a business that’s quite innovative, there’s not really a comparable [case], so you don’t want someone who’s transferring what he’s seeing from his past experience into your business. You want someone who’s thinking outside the box,” he said at Index’s private event in September. “In my mind, the important thing is to try to find the right balance: candidates with some experience in a start-up environment, perhaps someone who has run a department or a country but not of the same size. They will see it as a step up, something new, and won’t necessarily try to impose a certain way of thinking but be open to new ideas.”

In practice, this attitude means embracing risks. It also means accepting failures, as long as they come from a bias to action and trying to do the right thing. “I’ve learned a lot in the last year here, way more than I have in any other job,” says David Scott, Deliveroo’s Operations Director for the UK and Ireland, who worked for nearly 10 years in a series of senior strategy roles at Tesco. “So many mistakes I’ve made, so many things I’ve done wrong, so many things to learn from to get right in the future.”

Deliveroo also has a huge community to keep informed and on-side, from customers, restaurants and riders in particular. “Riders are at the heart of what we do,” says Scott. “For someone interested in this kind of work we have to make Deliveroo the number one choice, the most flexible, with the best pay.”

When it comes to recruitment, finding the balance between expertise and experimentation is crucial. He thinks it’s dangerous to go to either extreme, as experience and ambition sometimes work against each other. - Roy Blanga, Managing Director of International at Deliveroo

George Pallis, Deliveroo’s Director of Marketing, saw riders as central to the objectives of the rebrand. “One of the key drivers to making a change on the brand was to make them feel proud about what they do, make sure they are safe, make sure they know this community cares about them,” he said at Index’s private event in September. “The drivers are the lifeblood of the business… We want to optimise our model based on what works for them.”

George Pallis, Deliveroo’s Director of Marketing

Another aspect of the redesign was to showcase how much Deliveroo cared about the food itself and the people who make it. The new look includes massive close-ups on the detail of dishes, including salads, icecreams, and a huge hamburger that takes up the entire side of a double-decker London bus, emblazoned as part of the marketing campaign. “A big emphasis after our new look is zooming into the food,” Pallis says. “It’s not about ‘consuming’, it’s about sitting with your friends and your family, with the ability to order a t-bone steak or a grilled fish. It’s that spectrum of choice.”

Many employees talk about how Deliveroo’s presence in the urban streetscape is both a nice reminder of their work and an antidote to self-satisfaction. “The physical nature of the company keeps us grounded, it’s hard to remove ourselves from our operations,” Rohrbach says. “If you build a photo-sharing app and you move around a button, it might affect one or two metrics. But say you take a design decision that encourages people to order more lunch. You need to ensure there are riders to cater for that, and coordinate with the account management teams to make sure the restaurants are on the same page. That degree of logistical complexity and scale internationally is unheard of in the startup world.”

Where to now?

At this stage in a company’s growth, self-satisfaction and complacency are a risk. “It would be easy to say, ‘Look, that’s amazing, my work is driving all around London,’” says Rohrbach. “But I’ve never had that thought; it completely misses the point. The work should only be judged on the merit of the experience it delivers, and there’s still so much more we have to do to.” Rohrbach still worries about every single order that shakes around en route, “because we go over cobbled streets and we haven’t made the box soft enough yet,” Rohrbach says.

D’Angelo is working on “opening up the kitchen” digitally, recreating the experience of the intimate conversation you might have with the head chef at an exclusive restaurant. She and her team have created a series of “Meet the Chefs” profiles, which showcases the likes of Jamie Oliver and Fred Smith, the head chef of the BYRON burger franchise. “We don’t just deliver-oo, we help you explore,” she says. “Food is super personal. You have the old adage that something is cooked with love, and you can tell.” In restaurants, food can become quite instrumental and service-oriented, rather than fostering a connection between diners and chefs, d’Angelo says. But Deliveroo hopes to change that. “These chefs have spent years crafting a skill, which they use every single time they’re chopping up their onions.”

Each employee has the opportunity to bring their own passions and interests to bear on their work, if they can take the company forward. Cooper is fascinated by behavioural economics and the work of Nobel prizewinner Daniel Kahneman. He presented a lecture on the subject to his team at one of their regular knowledge-sharing sessions. Kahneman’s work shows how “present bias” can incline us to making make poorer choices – that when we pick something that we are going to experience far in the future, we make the more “rational” or virtuous choice, but when we are choosing something that we want right now we’re more likely to give in to desires and habits. “When it comes to eating food, maybe we should be encouraging people to order in advance, because we know they’re more likely, statistically speaking, to choose a healthier dish,” Cooper says. “This is really interesting and unexplored terrain for Deliveroo.”

Perhaps the company’s most interesting new initiative is called Editions, which brings pop-up kitchens to areas where the food selection is scarce. They start by fitting out a new site, such as a shipping container, with a fully equipped kitchen optimised for delivery. Restaurants can then use these sites as a temporary outpost, with each Editions kitchen accommodating between five and ten different restaurants. Deliveroo plans to open Editions in 30 locations across the UK this year. “We can instantaneously switch on demand for them, without all the capital and marketing costs,” says Pradhan, who runs the project. The idea is to generate a virtuous cycle in which expanding the creative palette for new and emerging restaurants increases the choice and supply for consumers, which in turn pushes up demand.

Editions can be seen as part of an evolution of the food industry as a whole. Phase one was picking up the phone. Phase two involved online marketplaces that connected consumers to restaurants but without operating any of the logistics, while phase three was Deliveroo in its first iteration. Now comes phase four, with sites that are optimised for delivery, optimised for customer experience, and optimised for potentially bringing down the price for the consumer as well.

“I am convinced that Deliveroo has several opportunities to effect real change, beyond bringing us great food in 30 minutes,” says Rimer, of Index Ventures. “Connecting people through food, helping small businesses serve more customers, bringing great food to food deserts, bringing tens of thousands of riders into the workforce, are all very real objectives.”

Posted on 16 Jun 2017

Published — June 16, 2017

-

-