Trade Winds: The Rise, Reckoning and Reimagining of Vlad Tenev

When Vlad Tenev was seven, his father gave him a copy of Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time.

A popular science classic, it explores the origins, structure, and fate of the universe, using non-technical language to make concepts like black holes and quantum theory accessible to general readers. Even so, it’s heady material for most third-graders.

In the evenings, Tenev’s father would come home and ask questions about the book. “Basically, he would grill me,” Tenev recalls. Although he was an economics professor, not a scientist or mathematician, Tenev’s father wanted to nurture his son’s growing interests. Neither of them could have imagined how those late-night talks would shape not only Vlad’s path but the financial lives of millions around the world.

“That book got me thinking about the big questions,” Tenev says, “The origin of the universe, what happened before the Big Bang, the laws that govern physics. Even as an entrepreneur, I think what drives me is just trying to understand how the world works.”

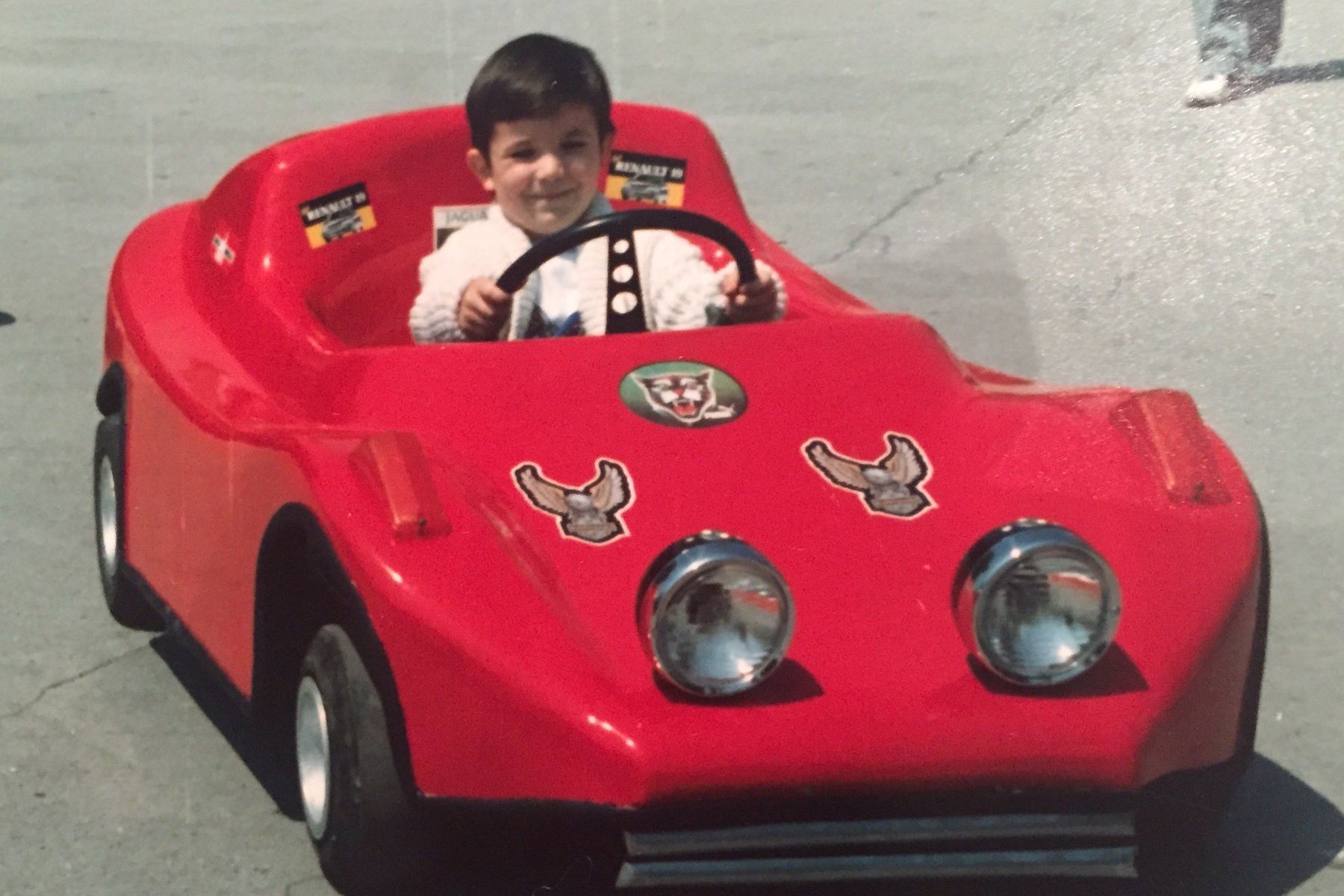

Tenev’s own story originates in Varna, Bulgaria, a former Communist state, shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall. In 1990, when Vlad was three, his father was offered a chance to study at the University of Delaware. The family couldn’t afford to send everyone, so his father went first, followed by his mother a year later. Six months after that, five-year-old Vlad boarded a plane for the first time, landing at JFK to be reunited with his parents.

The family lived with another Bulgarian family in Newark, Delaware. After Tenev’s father got accepted into a PhD program at the University of Maryland, they moved into student housing in College Park. Tenev remembers a photo album with a picture of his father’s first U.S. earnings—a smattering of coins and bills laid out on a bed. “He was so proud to get some money in this new country in the local currency,” he says.

For most of Tenev’s childhood, however, money was in short supply. The family had few books or toys, and he spent countless hours occupying himself. On nights when his father worked late, Vlad often tagged along, since they couldn’t afford a babysitter. It was in the UM computer lab that he taught himself how to use computers.

"Even as an entrepreneur, I think what drives me is just trying to understand how the world works.”

—Vlad Tenev, Robinhood

Tenev’s parents, he says, worked “extremely hard,” and eventually they bought a house in Alexandria, Virginia. However, as the only child of immigrants, Vlad grew up under constant pressure to excel academically. “My parents’ status as visa holders always seemed fragile,” he says. “They had taken this huge risk leaving Bulgaria and their support system—leaving just in time, with no money, right before the economy collapsed. That risk was juxtaposed with a more conservative mindset when it came to my education and opportunities.”

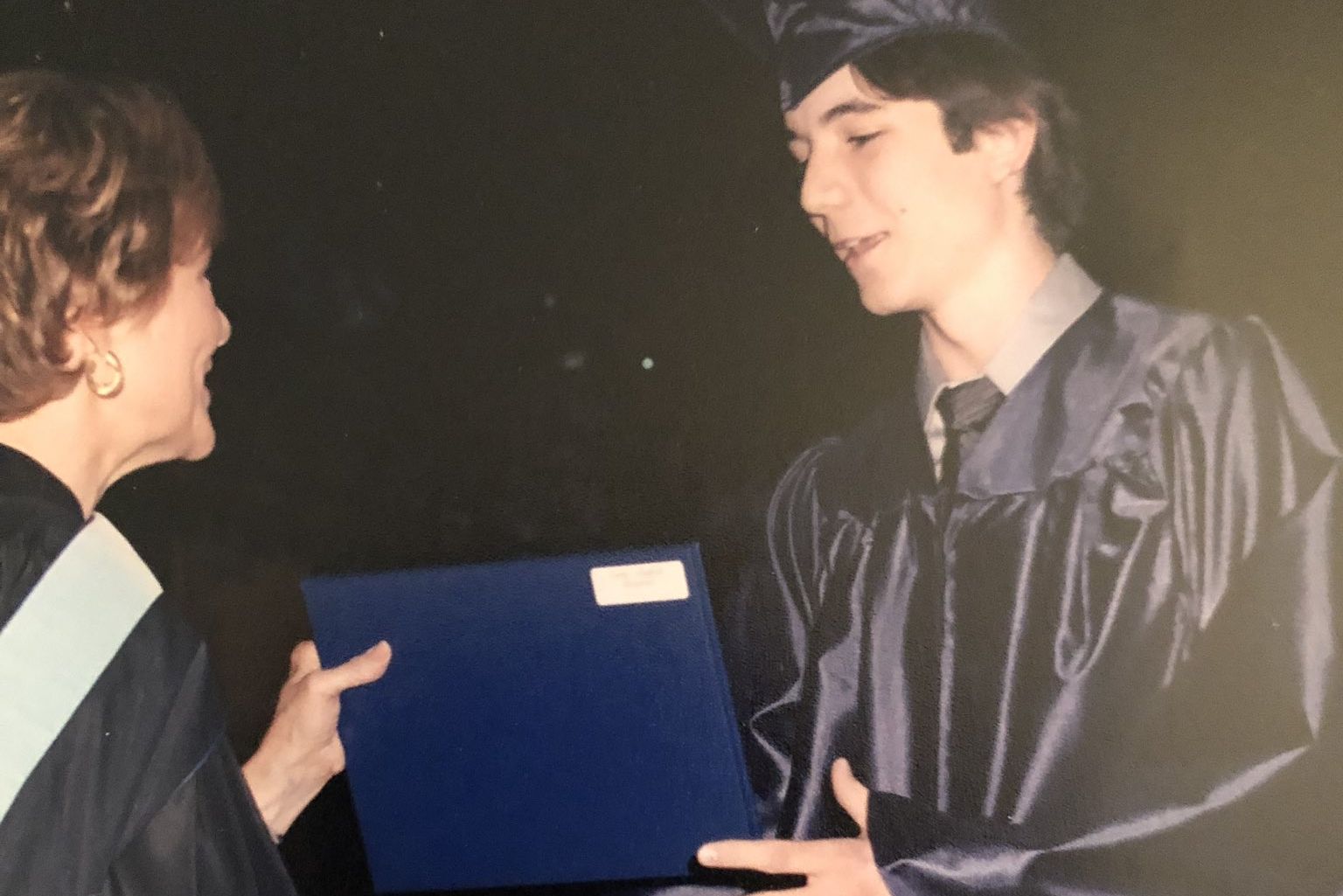

Fortunately, Vlad performed well in school, demonstrating an early talent for math and computers. After toying with the idea of becoming a lawyer (inspired by the Tom Cruise movie A Few Good Men), he enrolled at Stanford to study mathematics. It was there, during a summer physics program, that he met Baiju Bhatt. Bhatt was a few years older, but they shared several similarities: both were only children, both grew up in Virginia, both were raised in immigrant households, with what Tenev calls “similar pressures.”

“We both had childhoods where much was expected of us,” he says. “We both liked to challenge ourselves by taking these very difficult graduate-level classes that you would get no credit for, either from your school, your peers, or prospective employers.”

The two became fast friends, moving into a house off campus in Menlo Park. “Baiju decorated our place very nicely,” Tenev says. “He always had very good taste. He knew what he liked and what he didn’t like. He could articulate that very, very clearly.”

Tenev graduated in 2008—right into a global financial crisis. He applied for jobs as a derivative trader. He applied for jobs at Google. “Nobody wanted to hire me,” he says.

He decided to return to school, enrolling in UCLA’s PhD program in mathematics. But as much as he enjoyed math, he began to question whether it was the career for him. Someone gave him a copy of A Mathematician’s Survival Guide, a book ostensibly about navigating the bureaucracy of a university math department. “It dawned on me that this was a job like any other job, with a lot of stuff you had to do that was not research,” he says.

One day, he received a phone call from Bhatt, who, a few months earlier, had started a job at a high-frequency trading firm in Marin County. As Tenev notes, “It just so happened that an electronic trading revolution also began at around that time.”

“I see an opportunity here,” Bhatt told him. “I think we could create our own firm.”

“I wasn’t having an amazing time at grad school,” Tenev recalls. “So I thought, ‘Why not? Let’s give it a try.”

Tenev took a leave of absence, and the two rented a house in South San Francisco. In 2010, they founded their first company, Celeris, building high-frequency trading software. “I would work all hours that I wasn’t eating or sleeping,” Tenev says. “I poured my heart and soul into it.” While the venture never took off commercially, for Tenev, it did much more than that—it served as a reminder of the freedom and creativity he had felt while solving math problems.

“The objective of math is to create a new theory, make a new discovery,” he says. “All you need is your brain, a nice couch that you can lie on and close your eyes, maybe a chalkboard if you want to collaborate with someone or write something down. It’s a very efficient way of taking what’s in your mind and turning it into output.”

In entrepreneurship, he had found something similar: “Just taking all my energy to produce something, working for myself and not being beholden to anyone besides the customer—that was very intoxicating. It was so exhilarating that, even though we weren’t having any material success, it was enough for me to say, "This is my path. This is what I want to be."

Just taking all my energy to produce something, working for myself and not being beholden to anyone besides the customer—that was very intoxicating. It was so exhilarating that, even though we weren’t having any material success, it was enough for me to say, 'This is my path. This is what I want to be.'Vlad Tenev,

A Seat at the Table

The early highs of entrepreneurship lasted about a year before Tenev once again felt the pressure of living up to expectations. “My friends and family were starting to talk about whether I made the right decision,” he says. “I knew I needed to work on something commercially successful and start generating some revenue.”

In early 2011, Tenev and Bhatt abandoned Celeris to launch their second venture, Chronos Research. By that point, they had relocated to New York City. They bootstrapped the business, selling algorithmic trading software to banks and hedge funds. In about a year, they grew revenue to a few million. But something was missing. “If I keep working on this for 30 or 40 years and it reaches its logical conclusion,” Tenev asked himself, “will I be proud to tell my grandchildren? Would I want this to be my legacy?”

“Chronos didn’t really do that for me,” he says. “But Robinhood did.”

By 2013, the convergence of a few trends had sparked the idea for a new business. One was the rise of electronic trading. Another was the emergence of smartphones and mobile-first companies like Uber and Instagram. Tenev and Bhatt saw a particular opportunity to serve Millennials, who had grown distrustful of financial institutions after the Great Recession. Populist movements, such as Occupy Wall Street, had channeled that frustration into a broader demand for transparency, fairness, and access, particularly when it came to money.

That same year, Index partner Jan Hammer was introduced to Tenev and Bhatt through a series of connections at General Atlantic, where he had previously been an investor. They met via Google Hangouts, and Tenev and Bhatt showed him an early version of a mobile app where users could discuss stocks and predict trading activity. Hammer was impressed by its early engagement and slick UI. Although they weren’t yet planning to offer trading, he was also reminded of a shift he had seen at E*TRADE, a pioneer in the transition from brick-and-mortar brokerages to self-service via the phone and internet.

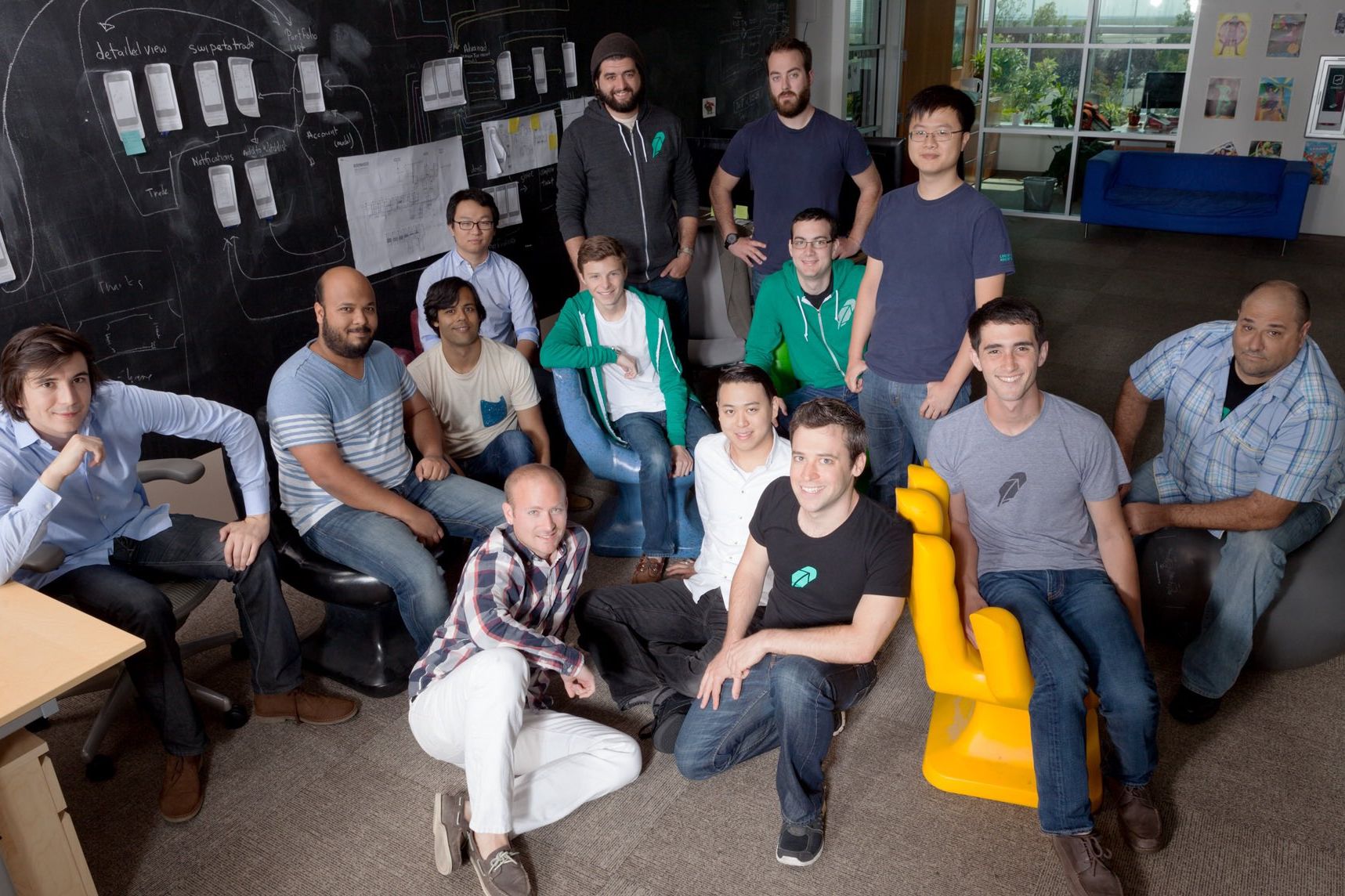

Robinhood co-founders Baiju Bhatt and Vlad Tenev

“The vision was, essentially, stocks on mobile for millennials,” Hammer says. “Millennials were the wedge—not unlike Amazon selling books and then selling everything to everyone.”

In October 2013, Index invested $500,000 in Robinhood, becoming the company’s largest seed investor. By then, Tenev and Bhatt had moved back to the Bay Area. On Hammer’s monthly trips from London to Index’s new San Francisco office, he made a habit of stopping in Redwood Shores and spending time with Tenev and Bhatt. He found them both creative, resourceful, “par excellence examples of technical founders.” He highlights their first-principles approach to problem-solving, comparing it to Matt Damon’s character in The Martian: “If they didn’t know the answer to a problem, their general mindset was, ‘Let’s engineer the shit out of it.’”

“They divided the division of labor well,” he adds. “Vlad was more on the backend, infra, systems side of things, working with engineers. Baiju was focused on the user experience, working with designers, figuring out what the app should look like.”

“If they didn’t know the answer to a problem, their general mindset was, ‘Let’s engineer the shit out of it.’”

—Jan Hammer, Index Ventures

After deciding to create a mobile brokerage, the founders made a decision that was unheard of at the time: trading would be commission-free. As Tenev explains, “The electronic trading revolution had driven costs way down on the institutional side. Banks and hedge funds were effectively trading for free. But retail investors were still paying $10 per trade.” By automating more of the process and eliminating fees, they believed they could reach a much broader audience and help everyday investors build more wealth over time.

They were right. On the day they announced the app, thousands of people joined the waitlist. It went viral on Reddit and hit number one on Hacker News. Within a month, they had 50,000 signups. In total, nearly a million people would join the list.

In the spring of 2014, a few months before the trading app’s release, Tenev, Bhatt, and Hammer met at Antonio’s Nut House, a dive bar in Palo Alto. They shook hands on a $13 million Series A—though not without some intense negotiations. Hammer laughs as he recalls going back and forth with a 26-year-old Tenev, who insisted the company would be worth “not just billions, but dozens of billions.”

“Vlad has always been incredibly ambitious,” Hammer says. “And he’s an excellent negotiator.”

Robinhood co-founders Vlad Tenev (left) and Baiju Bhatt (right) with Index Partner Jan Hammer (center)

The app launched in the iOS App Store on December 11th. Hundreds of thousands of people on the waitlist converted to users. By October of 2015, it had processed over $1 billion in transactions. In 2018, the platform surpassed 4 million users—overtaking E*TRADE—and in 2019, four years after Robinhood introduced commission-free trading, incumbents like Charles Schwab, TD Ameritrade, and Fidelity followed suit. It was proof that the financial system could be rebuilt from first principles, access could be opened, and millions of everyday investors, not just institutions, could find a seat at the table.

The Cost of Growth

By 2019, Robinhood had grown to around 700 employees and nearly $300 million in annual revenue. They faced the usual challenges of any startup at that stage—how to scale the business, achieve sustainable profitability, and when to go public.

“And then COVID came,” Tenev says. “And it just blindsided everyone.”

In the first weeks of the pandemic, global markets plummeted. The S&P 500 fell more than 30% from its peak in just over a month. As the world shifted to remote work overnight, hundreds of companies announced layoffs, slashed budgets, and scrambled to preserve cash.

“Everyone was telling us there was going to be this depression, that we had to be really nimble in how we operated,” Tenev says. “But our business was going through the roof.”

As the pandemic took hold, trading volume surged. Millions of investors opened Robinhood accounts, and deposits hit all-time highs. The company nearly tripled its revenue from the previous year, ending 2020 with almost a billion dollars in revenue. “We were doing as much as humanly possible to meet demand and stay alive,” Tenev recalls.

On March 2nd, the platform suffered a nearly full-day trading outage. In the aftermath, the team threw everything it had at the problem—its best engineers and all available resources—to ensure they could handle the load. But each day still felt precarious.

“There was this constant fear every evening of whether market open would go smoothly,” recalls Abhishek Fatehpuria, Robinhood’s VP of Product. “You would have all these people up at 6:30 every morning, huddled around computers, making sure we were staying up. It felt like we were constantly firefighting, because we were growing so fast.”

“[Tenev and Bhatt] basically said, ‘We’re going to sacrifice near-term growth for a cautious approach'.... It provided a springboard for repairing relations with regulators and gave Robinhood a platform for further growth."

—Jan Hammer, Index Ventures

To keep pace, the company embarked on a hiring spree, tripling its headcount by the end of 2020 and nearly doubling it again a year later, finishing 2021 with a workforce of close to 4,000 employees. Before the pandemic, Robinhood had what Fatehpuria calls a “very rich in-person culture.” However, that culture radically changed as the company onboarded thousands of employees who had never met their teammates face-to-face. “Growing a team by that much in that short of a window is really hard, especially when you don’t have your culture to lean back on.”

Robinhood was hardly alone in getting swept up by the new macro environment. Money was cheap, interest rates were zero, and valuations were soaring. Startups everywhere were growing fast, and investors were rewarding scale over discipline.

“You didn’t have to do a lot of the things that you traditionally think make great companies,” Tenev says. “We got a little bit out of the realm of effectiveness and efficiency.”

That lack of discipline caught up to them in early 2022, when the easy money era ended almost as quickly as it had begun. “Interest rates went up, money got tight, inflation got high, and the macro environment shifted from very, very loose to very, very tight,” Tenev explains. “Things that were necessary in one regime did not help us in this new regime.”

Trading activity plummeted, the S&P 500 entered bear market territory, and Robinhood—which had IPOed at $38 per share in July 2021—saw its stock price fall below $10. In the first quarter of 2022, the company reported a 43% year-over-year decrease in net revenue.

At the same time, regulatory scrutiny was intensifying. A string of controversies had drawn attention from watchdogs and lawmakers, prompting a deeper examination of the company’s business model, internal controls, and relationship with its user base. “Lawyers and regulators and compliance people started crawling all over the company,” Hammer says.

The company retrenched, taking every step necessary to ensure compliance. “They went cleaner than clean,” Hammer says. “They basically said, ‘We’re going to sacrifice near-term growth for a cautious approach.”

That decision paid dividends down the line. “It provided a springboard for repairing relations with regulators and gave Robinhood a platform for further growth,” Hammer adds.

“We did what we needed to adapt to the new regime. Today, those winds that were blowing against us are actually blowing with us.”

—Vlad Tenev, Robinhood

Becoming compliant was part of a broader effort to strengthen operations. “We didn’t want to be the kind of company that just waits for the macro environment to shift,” Tenev says. “Instead, we said, ‘How can we thrive in this environment? Let’s say this goes on forever—high interest rates, tight monetary policy. How do we make sure Robinhood wins in that environment?”

The first step, as Fatehpuria puts it, was making sure the team was “appropriately staffed.” Over two rounds of layoffs, the company reduced headcount by over 1,000 employees. “It was excruciating,” Tenev says. “But then you see the effect it has on the company. Even though it was painful, it was very, very good over the long run.” Fatehpuria agrees, adding, “With smaller, more focused teams, we were happier and more productive.”

They also did some strategic soul-searching. For years, Robinhood had centered its efforts on first-time investors. But in a downturn, it became clear that the core of the business was active traders—those with experience, more complex strategies, and a deeper commitment to the markets. “By choosing to focus on active traders for a few years at a really high concentration of the company, we’ve been able to solidify the business, and the core business became a lot stronger and more sustainable,” Fatehpuria says.

“It was tough, but we grew a lot. We survived, and we’re better for it.”

—Abhishek Fatehpuria, Robinhood’s VP of Product

By 2024, Robinhood had become profitable in a high-interest-rate, tight-liquidity environment. More recent shifts, like easing rates, renewed retail interest, and a more innovation-friendly regulatory climate, have created what Tenev calls a “double tailwind” for the business. “We did what we needed to adapt to the new regime,” he says. “Today, those winds that were blowing against us are actually blowing with us.”

“A lot of how we tell our story now is the culmination of the past two or three years of work,” Fatehpuria says. “It was tough, but we grew a lot. We survived, and we’re better for it.”

Anchor in the Storm

In 2018, Dan Gallagher got a call from his friend Joe Grundfest, a Stanford law professor and fellow former SEC commissioner. Grundfest asked if Gallagher, a veteran brokerage lawyer, would meet Robinhood’s founders and offer guidance on some issues they were facing in Washington, D.C. Gallagher, who had first encountered the company during his time at the SEC, admits he “wasn’t too keen to meet them.”

At Grundfest’s urging, Gallagher eventually agreed to a meeting in 2019. “It immediately became clear they were misportrayed in Washington,” he says. While Tenev and Bhatt had been painted as “two 20-year-olds trying to replicate the Uber model—break rules and ask forgiveness later,” he found them thoughtful, charming, and “if anything, overly respectful.”

In the summer of 2020, two months after joining Robinhood as Chief Legal Officer, Gallagher had the first of many tough conversations with his new bosses. “They were just incredibly deferential and never wanted to argue,” he recalls. “So I said, ‘Guys, you really gotta start pushing back on stuff.’” Tenev and Bhatt were quiet for a moment, then looked at each other and started laughing. They confessed to Gallagher that they were scared of him. “That kind of level-set our relationship going forward,” he says with a smile.

Robinhood's Chief Brokerage Officer Steve Quirk, CEO Vlad Tenev, CFO Jason Warnick, and Chief Legal Officer Dan Gallagher on Robinhood's NASDAQ debut in July 2021

Gallagher had been drawn in by Robinhood’s mission, but it was Tenev and Bhatt as leaders who convinced him to join. “I found they made a really great pair,” he says. “You have the more extroverted Baiju and the more introverted Vlad, but both are incredibly smart, incredibly motivated about Robinhood, and deep down, just really, really nice people.”

Tenev and Bhatt served as co-CEOs until November 2020, when Bhatt stepped down to become Chief Creative Officer. (He has since left day-to-day duties at Robinhood, founding a new company, Aetherflux, which raised a $50 million Series A led by Index in April 2025. Gallagher joined Aetherlux’s board soon after.)

Since then, Gallagher has watched Tenev lead the company through more crises than most founders face in a lifetime. In November 2021, just a few months after the company went public, an attacker gained access to the names and email addresses of millions of Robinhood users. “I’m used to crises—I’ve been through a million of them,” Gallagher says. “But if I were CEO of a public company and we had a breach event, I’d be running around like crazy.” Instead, he recalls Tenev being “cool as a cucumber.”

He looks at the whole ocean, not just the waves around him.Jan Hammer,

Partner at Index Ventures

“He was an amazing field general throughout that process,” Gallagher adds. “Just his acumen, his knowledge of how the company runs, being able to ask questions of the security team, outside consultants, lawyers. When you’re dealing with a crisis like that with lots of unknowns, it’s pretty awesome to have the person in charge remain that calm.”

Fatehpuria, who joined Robinhood in 2016, has seen firsthand how the CEO’s calm demeanor helps the team in stressful situations. “He treats things seriously, but he doesn’t act too seriously,” Fatehpuria says. “He’s very even-keeled—taking issues as they come, hearing all the points of view, and then making a decision.”

Through Robinhood’s toughest moments—the outages, the regulatory scrutiny, the public backlash amid the 2021 Gamestop saga—Hammer credits Tenev with keeping perspective. “He looks at the whole ocean, not just the waves around him. Even when the share price was at its lowest, he always knew performance would improve, brand perception would recover, and new products would come on stream. It speaks to his time horizon.”

Vlad Tenev with Index Partner Jan Hammer

Tenev admits it hasn’t always been easy. “There have been many times when I’ve lost sleep,” he says. But he’s learned the difference between situations you can push through and more nuanced ones that demand tough decisions. “Some problems, like Gamestop, you just put one foot in front of the other and keep going. Others involve a bit more strategy, and the source of stress is letting it linger when you know you should be doing something about it.”

With experience, he says, comes confidence. “At this point, I’ve seen so many different situations. A business problem that 25-year-old Vlad would have freaked out about and spent months trying to navigate, I can just kind of deal with in the background.”

"He loves truth-telling. He loves data and information. He really wants to understand your view. It’s part of his scientific process—his first-principles approach to everything."

—Dan Gallagher, Robinhood Chief Legal, Compliance and Corporate Affairs Officer

That confidence, Gallagher says, has translated to the boardroom. “It’s not a debate club anymore. It’s Vlad’s vision—where he wants to take the company, how he’s going to do it. He’s much more directional. The board appreciates that. Obviously, he still takes feedback, but he exudes confidence. And our record is proving that his vision is what the company needs.”

Gallagher emphasizes Tenev’s willingness to take feedback. “You could tell him almost anything, even if it’s really negative, and he’ll say, ‘I’ll take that feedback.’ And he’ll think about it and try to improve based on it. He doesn’t hold a grudge. He won’t skip your next meeting. He loves truth-telling. He loves data and information. He really wants to understand your view. It’s part of his scientific process—his first-principles approach to everything.”

Hammer recalls many instances when Tenev has come to him, often in the company’s darkest moments, seeking to become a better leader. “Vlad is someone who’s prepared to change if that’s what the business necessitates,” Hammer says.

Of all the lessons, Tenev says the most important has been finding focus. “I like to do a lot of things, and I can be rather impatient. I ask myself, ‘Am I actually solving the problem? Or am I just visiting it, not really solving it, and then moving on to the next one, collecting problems?” It’s a lesson he’s trying to teach his three children, one he believes matters more than ever. “My childhood was pretty simple. There weren’t many things competing for my attention. Now, kids have it tougher. Focusing and going deep on one thing is much rarer and more important.”

Behind the press clippings, the controversies, the now-seasoned face on CNBC, Gallagher says, is a kind, devoted, big-hearted leader. “When you spend time with Vlad, you realize how nice he is. He’s a family guy. He remembers things you told him years ago and brings them up in conversation. He’s just very thoughtful.”

In 2021, when Fatehpuria took a two-month medical leave, he says Tenev called his family and put him in touch with doctors. “I would come into the office, and we would shoot hoops while I was recovering,” Fatehpuria remembers. “He would check in and make sure I was resting and not working. It revealed a great deal about his character and who he is as a person. He cares about people. That’s why people like working with him.”

Creating a Legacy

Tenev still has memories of his early childhood in Communist Bulgaria. It’s a stark contrast to the technological, scientific, and political upheaval of today. Tomorrow will look different, but with all the change, he says, one thing that isn’t going away is money.

“People are going to have money, they’re going to invest their money, they’re going to need to save for the future,” he says. “The service Robinhood provides is very durable and is going to be even more valuable in the future than it is today. If we can provide that service capably to millions of people and just keep getting better, we can build a very special company.”

Hammer sees Robinhood’s story as a circle. “You start as a startup, you’ve got nothing, and you say, ‘I’m going to change the world.’ Then you become big and corporate, and you have to obey regulations, and growth slows down. Now, are you a leader, or are you an also-ran?”

For any scaleup, Hammer says, there comes a crossroads. You can keep doing what you’re doing, try to expand in the margins, or you can go “full arc” like Robinhood. “They’ve leapfrogged by being bold and going back to their roots—reimagine finance, disrupt everything.”

“You have to dream what the next big thing could be. Vlad has certainly been a visionary.”

—Jan Hammer, Index Ventures

More than a decade after Tenev predicted that Robinhood would be worth “dozens of billions,” the company is nearing a $100 billion market capitalization and is set to be included in the S&P 500. It recently announced a major push into tokenized assets, offering EU customers 24/5 trading on tokens providing exposure to hundreds of stocks and ETFs. The company also gave away stock tokens that reference private companies such as OpenAI and SpaceX. It’s part of the company’s broader goal of becoming the top global destination for active traders and a leader in blockchain-based investing.

“You have to dream what the next big thing could be,” Hammer says. “Vlad has certainly been a visionary.”

The most important thing is that I was working on something I was legitimately proud of. When it’s a mission you buy into and a product you really care about, you’re willing to put up with a lot—because you know that at the end of the day, this is your life’s work.Vlad Tenev,

Co-founder of Robinhood and Harmonic

Long before Tenev ever thought about entrepreneurship, he dreamed of becoming a mathematician. Part of what motivated him was creating a legacy: “If I was good enough and I created something interesting enough,” he says, “maybe in 30 or 40 years, kids would learn it, like the great mathematicians: Gauss, Riemann, Ramanujan.”

It was that same promise that drew him to entrepreneurship: “You can take what’s in your brain and turn it into a product. And if you’re lucky enough and good enough, that product can be used by tens of millions—maybe one day hundreds of millions, or billions of people.”

Tenev’s passion for mathematics hasn’t faded. In 2023, he co-founded Harmonic, an AI platform working to build mathematical superintelligence that solves complex problems more efficiently and accurately than existing AI technologies. In July 2025, the company announced a $100 million Series B, bringing its total funding to $175 million.

It’s already been a long journey for the 38-year-old founder, with plenty of ups and downs. “The most important thing,” he says, “is that I was working on something I was legitimately proud of. When it’s a mission you buy into and a product you really care about, you’re willing to put up with a lot—because you know that at the end of the day, this is your life’s work.”

Published — Oct. 1, 2025

-

-